When in doubt, send in a General from Missouri to save the world [part 2]

- Bob Ford

- Jan 30, 2025

- 5 min read

If you like history, we are seeking sponsors to support this column. We are keeping history alive so you can pass it on! Please contact Rob at the Globe, 417-334-9100, for details.

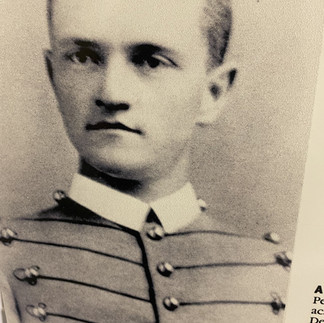

In 1917, General John J. “Black Jack'' Pershing was selected to command the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to save Europe. World War I had been a bloodbath stalemate since 1914. The world had never seen such carnage.

The Americans joined the war after President Wilson and Congress concluded now was the right time to step in and assist in saving the Allies from defeat then promote the ideals of the United States in a post Great War world.

Pershing’s first assignment was to build, train and supply a suitable force that would make a difference on the ground in Europe. As we prepared to enter, the U.S. army claimed 100,000 active soldiers, within a year the services recruited, trained and equipped two million soldiers. The army called them “Doughboys.”

“A competent leader can get effective service from poor troops while on the contrary, an incapable leader can demoralize the best troops,” Pershing famously said.

Some Americans had joined the fight earlier by aligning with other Allied armies. The British and French suffered monumental losses in their ranks and wanted the fresh U.S. troops to “fill the gaps.” Pershing took issue and through determination kept the newly arriving Americans together under one command—his.

Each new war is a continuation of previous wars with similar tactics and arms. In the case of World War I, armament developments outpaced strategies. Frontal assaults against an entrenched enemy continued. You would think lessons from the Civil War would have been learned.

The AEF’s first major battle with Pershing as sole commander was the Battle of Saint-Michel. This marked the first time in war where ground assaults and an air campaign coordinated efforts, and it worked. It just happened the Germans were retreating to another established line when the Americans and French attacked, which added to their success.

Nonetheless the victory convinced our Allies of Pershing’s capabilities and worth. The battle turned out to be the beginning of the end for Imperial Germany.

General George Marshall, Pershing’s Chief of Staff, is accredited after the battle with logistically pivoting the half a million-man army to the north joining other Allied forces in the final push of the War, the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The battle lasted 47 days until the Allies broke the Axis line at Sedan, France, on November 6, 1918. Germany formally surrendered five days later. The offensive was critical for overall victory but very costly. Allies loaded the trenches for the coordinated frontal assaults with 1.2 million soldiers, 380 tanks, 800 planes and 2,800 pieces of artillery versus the German line of approximately 450,000 men.

Remember all other countries but the United States had been fighting and losing soldiers at an incredible rate for years. Of the 1.2 million men committed, the Allies sustained 192,000 casualties with 122,000 being American. How many times in the annals of warfare had fresh troops made the difference in battles and wars…many. This was the case in World War I.

Pershing didn’t want an armistice. Even though he knew a ceasefire was imminent, Pershing ordered his officers to keep fighting. In the last days of the war the United States suffered 11,000 casualties, 26 years later on D-Day, our country endured 10,000 casualties. For that slaughter he would later face a congressional investigation and hearing.

Pershing knew Germany needed to surrender unconditionally, be occupied and demilitarized or “there would be another conflict in 25 years.” The Allies were sick of fighting and had unimaginable losses to deal with. Pershing was right, of course, but it only took 21 years until the start of World War II.

The Germans learned more from World War I than their adversaries. At the start of World War II, they initiated the blitzkrieg, no trench fighting stalemates now. Once their tanks and armored vehicles were in the open in Poland, 50-100 miles were taken every day with German troops several times fighting against men on horseback. Some countries learned and advanced while others licked their wounds from a last conflict and were vulnerable.

General Pershing had several famous military officers serve under him: future Generals Billy Mitchell, Patton, MacArthur, Marshall and stateside Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Many pre-famous notables also saw duty: Humphry Bogart, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemmingway, Edwin Hubble, Harry S. Truman, Walter Brennan, Thomas Hart Benton, Walt Disney and the Harlem Hellcats.

My favorite Great War movies include Stanley Kubrick’s classic “Paths of Glory" and Sam Mendez’s, two-take, cinematic gem “1917.” Hollywood usually likes wars, good material, but the two world wars were too close together to properly milk World War I.

For years the Great War, the war to end all wars, never got the historical respect it deserved. World War II overshadowed it, especially in this country. The United States lost 117,000 in the Great War but 405,000 in World War II, whereas Britain's casualties were three times higher in World War I than World War II and in France six times higher. Europe had not recovered from one war to get ready for the next; there were gaps in generations that made fielding armies to stop the Nazis difficult.

General John J. Pershing came home a hero. Congress made him only the second person, after George Washington, in U.S. history to be elevated and honored with the rank of “General of the Armies of the United States.”

After the war he became “Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army '' and took a leadership role in organizing the 20 American cemeteries that dot Europe and headed the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Pershing with his popularity had his hand in several things and was being pulled in many directions including a possible presidential run.

In 1922 as Secretary of War, there's a map in Laclede of the United States illustrating national roads needed between military installations to be able to move soldiers and equipment safely in times of crisis. That map became the National Highway Project and was turned over to little known Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower, welcome to the inception and planning of our interstate highway system.

A trip to the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City and Pershing’s Boyhood Home Museum in Laclede, MO, opens your eyes to the importance of the man and the “Great War,” that unfortunately did not turn out to be the war to end all wars.

![Missouri's Six-Star General [part 1]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/0d906d_f6390c5bc0df419eb0233bc3dcd99d20~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_735,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/0d906d_f6390c5bc0df419eb0233bc3dcd99d20~mv2.jpg)

Comments